G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute the largest superfamily of human cell surface transmembrane receptors with over 820 genes. They respond to a variety of ligands that include hormones, neurotransmitters, metabolites, ions, photons, and mechanical forces, with subsequent intracellular signaling relayed through G protein-dependent and -independent mechanisms. GPCR-triggered pathways are responsible for a plethora of physiological and pathophysiological effects, which is why approximately a third of all prescribed drugs target their activity. Of the more than 350 human GPCRs that are not sensory receptors, perhaps 140 are considered “orphan” receptors with no known ligand or function. Emphasizing their clinical value, it is thought that ~60-85% of potentially therapeutic GPCRs have no drugs directed at them.

GPCRs play a crucial role in the regulation of tissue/cell physiology and homeostasis in the immune, nervous, endocrine, and cardiovascular systems, among others. They also function in a multitude of pathological processes, including cancer.

GPCRs in cancers

Many GPCRs serve as potential biomarkers for early cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, GPCRs are active in various aspects of cancer progression, including proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, migration, and invasion. Therefore, the pharmacological inhibition of GPCRs and their downstream targets presents a promising avenue for developing novel, mechanism-based strategies for cancer therapy.

GPCRs in the immune system

Inflammatory cells such as leukocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells express more than one GPCR and sense a wide range of chemoattractants and chemokines. These receptors are crucial for the migration and infiltration of immune cells. Abnormal GPCR expression can lead to immune system dysfunction manifesting as inflammatory and autoimmune disease.

GPCRs in the nervous system

The nervous system utilizes membrane receptors to detect extracellular stimuli. By expressing GPCRs with diverse ligand-recognition capabilities, the nervous system can selectively filter and respond to specific signals. GPCRs are involved in chronic neurodegenerative diseases including but not limited to Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, and Parkinson's disease.

GGPCRs in homeostasis

GPCRs play a crucial role in maintaining metabolic balance by influencing key processes such as glucose homeostasis and insulin secretion, appetite, calcium sensing, heart rate, and blood pressure.

|

|

|

|

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638758.webp) |

|

Adenosine A1 Receptor antibody [HL2442]

|

|

GTX638758

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX636952.webp) |

|

Dopamine Receptor D2 antibody [HL1478]

|

|

GTX636952

|

|

|

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639345.webp) |

|

Somatostatin receptor 3 antibody [HL2681]

|

|

GTX639345

|

|

|

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639344.webp) |

|

Dopamine Receptor D1 antibody [HL2680]

|

|

GTX639344

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

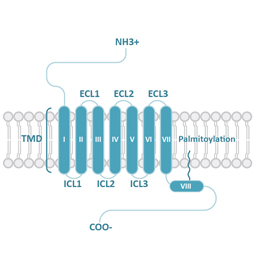

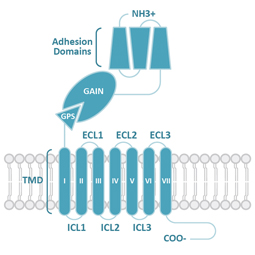

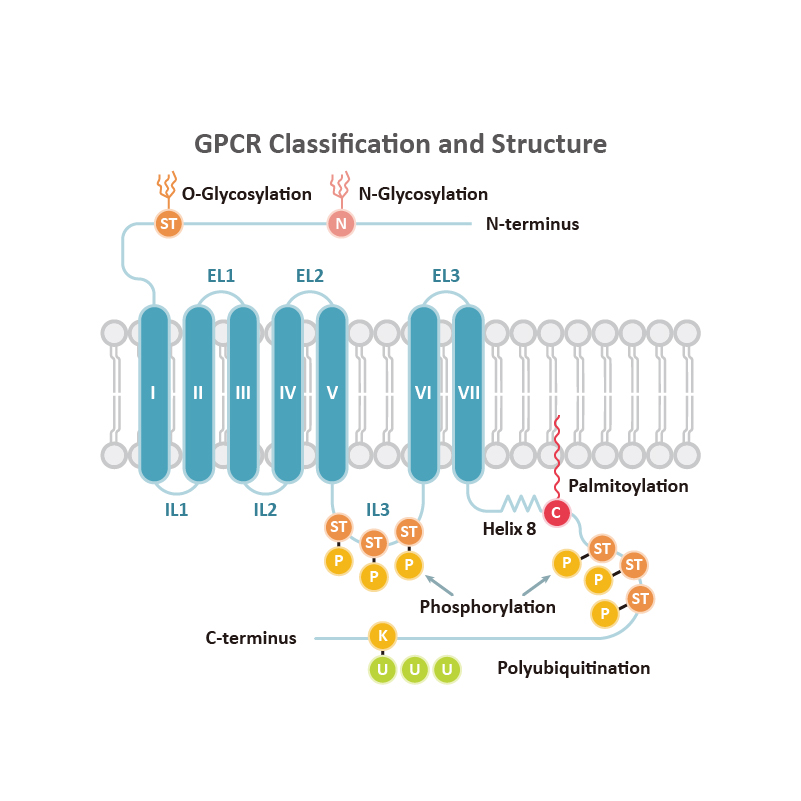

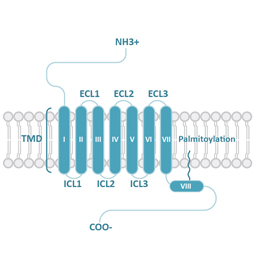

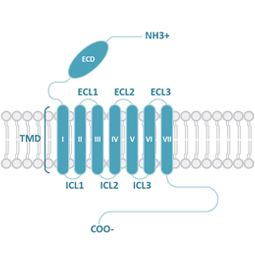

GPCRs share structural characteristics that include seven transmembrane (7TM) domains linked by both intra- and extracellular loops, an extracellular N-terminus, and an intracellular C-terminus. The loops, as well as the intra- and extracellular domains, are all subject to post-translational modifications. One widely used GPCR classification system is based on sequence homology and evolutionary relationships. This organizes GPCRs into six families designated A-F.

|

Family Class

|

General Structure (Adapted from Qu et al., 2020)

|

Ligand Interaction (Adapted from Xu et al., 2024)

|

|

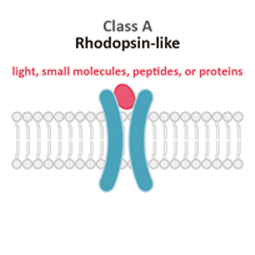

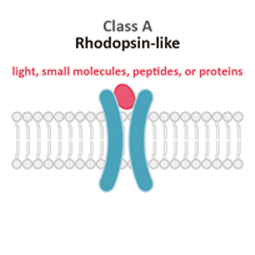

Class A

|

Rhodopsin-like (R)

Class A (Rhodopsin-like) GPCRs account for more than 85% of human GPCRs. This class is distinguished structurally by an additional palmitoylated 8th alpha helix.

|

|

|

|

|

Family Class

|

General Structure (Adapted from Qu et al., 2020)

|

Ligand Interaction (Adapted from Xu et al., 2024)

|

|

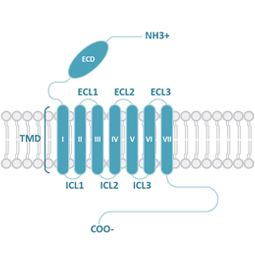

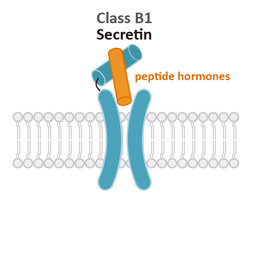

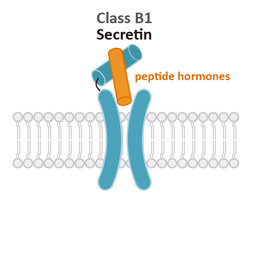

Class B1

|

Secretin (S)

Class B1 (Secretin) GPCRs are characterized by their large extracellular domains (ECDs) that are able to bind large peptidic ligands such as hormones or neuropeptides.

|

|

|

|

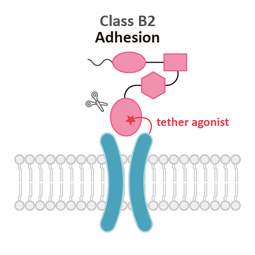

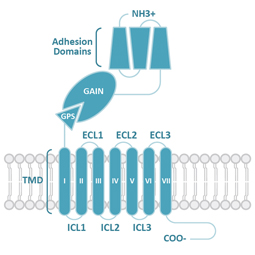

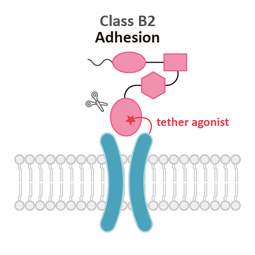

Class B2

|

Adhesion (A)

Similar to Class B1, Class B2 (Adhesion) GPCRs feature a large ECD. Signaling results from the pre-digestion of the GPCR autoproteolysis-inducing (GAIN) domain at the GPCR proteolytic site (GPS) motif. Mechanical force releases the Stachel peptide that then acts as a tethered agonist to bring about 7TM activation.

The individual N-terminal motifs of the subgroups reflect their unique roles in cell adhesion and migration.

|

|

|

|

|

Family Class

|

General Structure (Adapted from Qu et al., 2020)

|

Ligand Interaction (Adapted from Xu et al., 2024)

|

|

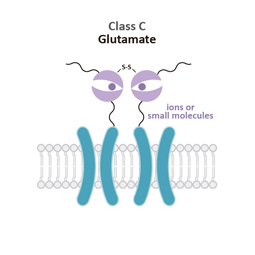

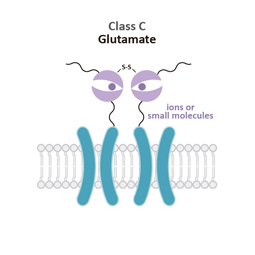

Class C

|

Glutamate (G)

Class C (Glutamate) GPCRs are distinctive for large ECDs, which include a Venus Fly Trap (VFT) domain and a cysteine-rich domain (CRD), and their mandatory homo- or heterodimerization.

|

|

|

|

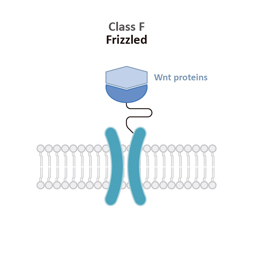

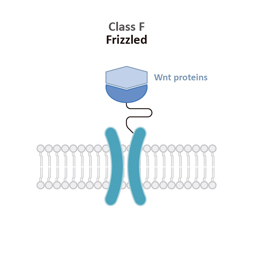

Class F

|

Frizzled (F)

Class F (Frizzled) GPCRs feature a cysteine-rich domain (CRD) and a linker domain (LD) in the ECD. Members of this class play roles in development and regeneration through activation of the downstream Wnt or Hh signaling transduction pathways.

|

|

|

|

![Calcium Sensing Receptor antibody [HL2357]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638563-1.webp) |

|

Calcium Sensing Receptor antibody [HL2357]

|

|

GTX638563

|

|

|

![Calcium Sensing Receptor antibody [HL2357]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638563-2.webp) |

|

Calcium Sensing Receptor antibody [HL2357]

|

|

GTX638563

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

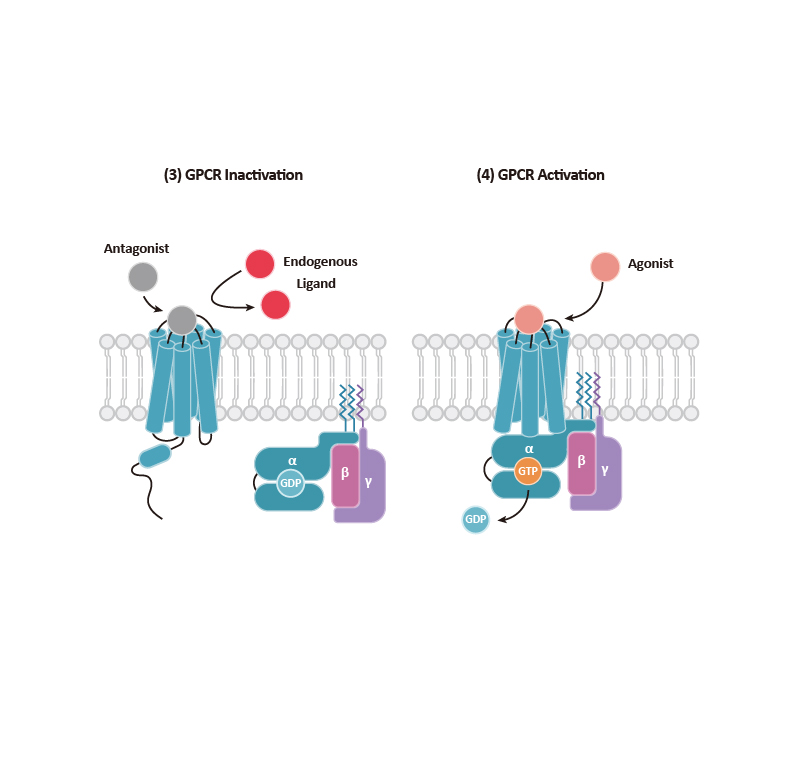

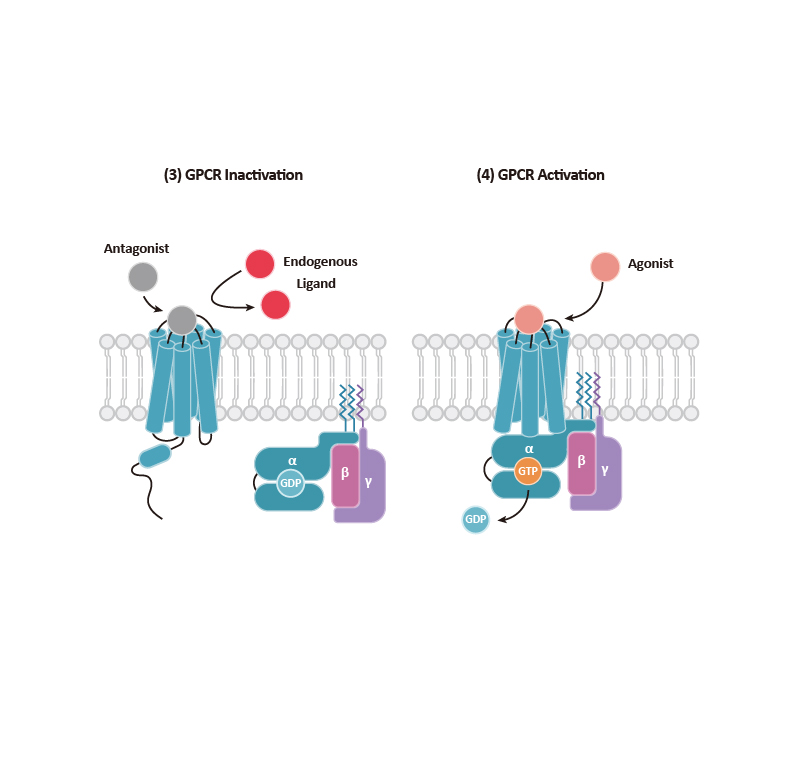

GPCR signaling begins with engagement of the receptor by a ligand, which leads to allosteric changes in the intracellular domains of the GPCR. In general, two types of effectors can then associate with the GPCR: (a) a Gα subunit that complexes with β and γ subunits to form the G protein trimer, and (b) β-arrestins that can direct their own signaling. It is becoming clear that GPCR signaling emanates not only from the cell surface but also from other intracellular compartments (e.g., endosomes, the Golgi apparatus, and the ER, among others). Signaling cascades involving kinases and transcription factor regulation orchestrate the subsequent cellular response.

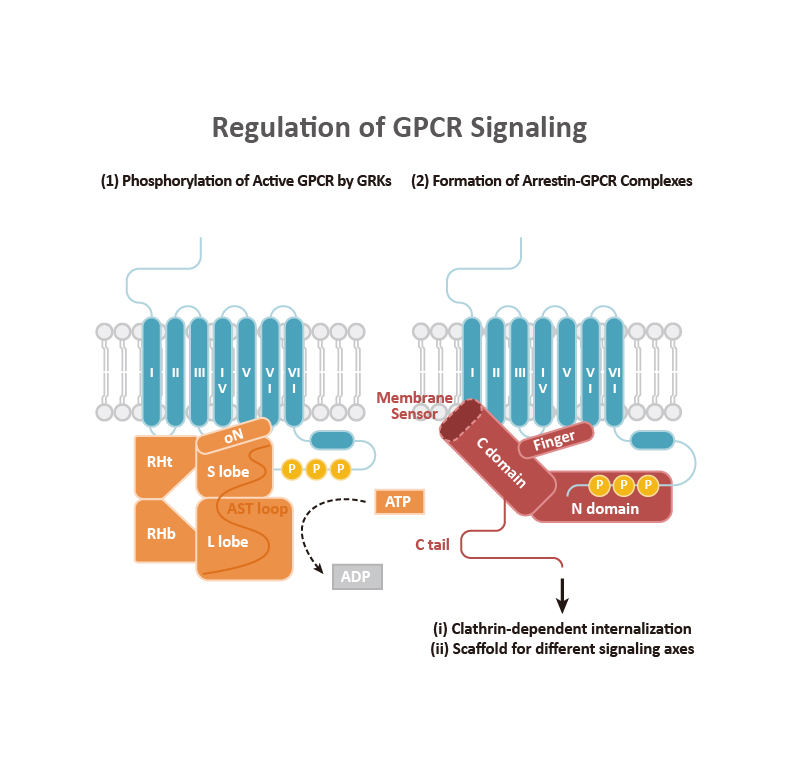

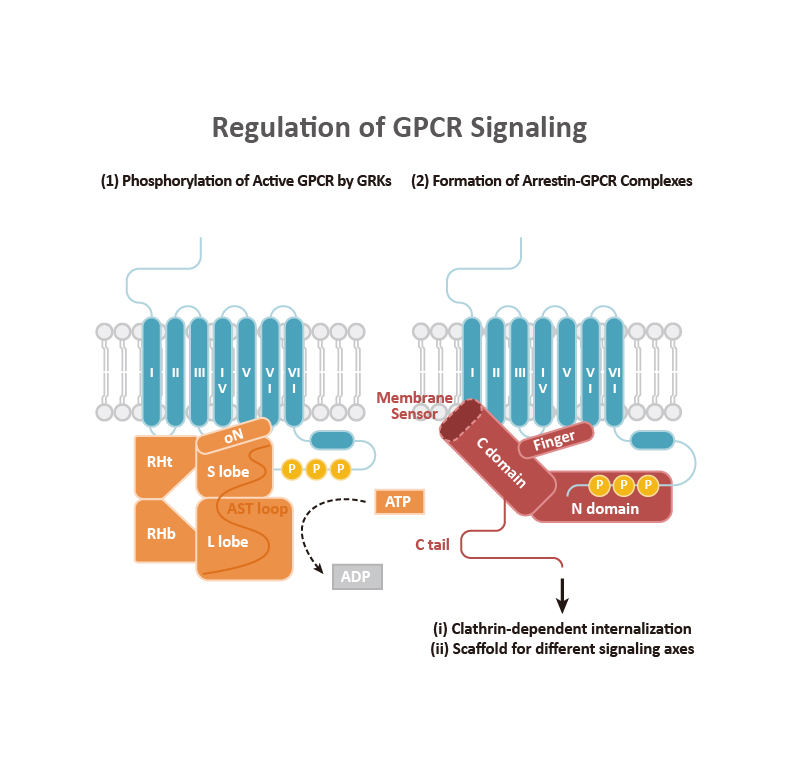

Classically, GPCR signaling undergoes termination through GTP hydrolysis and dissociation of Gα-Gβγ. G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) phosphorylate the C-terminal tail of GPCRs, facilitating the binding of the β-arrestins that, as mentioned above, can trigger their own signaling as well as contribute to GPCR desensitization and internalization. The GRK family, comprising seven kinases (GRK1-7), is categorized into three subfamilies: (1) the GRK1 subfamily consists of rhodopsin kinase (GRK1) and GRK7, (2) the GRK2 subfamily consists of β-adrenergic receptor kinase-1 and -2 (GRK2 and GRK3), and (3) the GRK4 subfamily consists of GRK4-6. GRK2, GRK3, GRK5, and GRK6 are key regulators of GPCRs. Beyond GRKs and arrestins, GPCR functions and signal transduction are influenced by GPCR-interacting proteins (GIPs) such as receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPS), regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins, GPCR-associated sorting proteins (GASPs), Homer proteins, and PDZ-scaffold proteins.

|

Protein

|

High-expressing tissues

|

|

GRK2

|

Bone marrow, spleen, lymph node, tonsil, and thymus

|

|

GRK3

|

Adipose tissue, spleen, cerebral cortex, tonsil, and hippocampus

|

|

GRK5

|

Heart muscle, lymph node, parathyroid gland, placenta, and gallbladder

|

|

GRK6

|

Bone marrow, lymph node, spleen, thymus, and granulocytes

|

|

β-arrestin1

|

Monocytes, cerebral cortex, pancreas, amygdala, and spleen

|

|

β-arrestin2

|

Bone marrow, spleen, granulocytes, liver, and monocytes

|

|

Adapted from Chen et al., 2021 and Shukla et al., 2013

|

Adapted from Cheng et al., 2023

|

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639338.webp)

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639056.webp)

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638646.webp)

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638758.webp)

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639328.webp)

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX636952.webp)

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639345.webp)

![CXCR1 antibody [HL2674]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639344.webp)

![GLP1R antibody [HL2297]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638352-1.webp)

![AGTR1 antibody [HL2524]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638885.webp)

![Rhodopsin antibody [HL2668]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639332-1.webp)

![Rhodopsin antibody [HL2668]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX639332-2.webp)

![CCR4 antibody[HL2492]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638850.webp)

![GLP1R antibody [HL2297]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638352-2.webp)

![GLP1R antibody [HL2297]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638352-3.webp)

![CD97 antibody [HL1925]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX637674-1.webp)

![CD97 antibody [HL1925]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX637674-2.webp)

![Calcium Sensing Receptor antibody [HL2357]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638563-1.webp)

![Calcium Sensing Receptor antibody [HL2357]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX638563-2.webp)

![Frizzled 9 antibody [HL1675]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX637274-1.webp)

![Frizzled 9 antibody [HL1675]](/upload/media/resources/Research Area/Cell Biology/G Protein-Coupled Receptors/GTX637274-2.webp)